How do you diagnosis and treat hemangiosarcoma in dogs?

Diagnosing hemangiosarcoma in dogs begins with a thorough physical exam by your veterinarian. If a tumor of the liver or spleen is large enough, your veterinarian may be able to feel it while palpating your dog’s abdomen. Your vet may suspect a cardiac tumor by listening to the heartbeat through the chest cavity.

An ultrasound is one of the best ways to confirm these kinds of tumors, but because hemangiosarcomas appear quickly, routine screenings for early detection are often cost-prohibitive. Other diagnostic tests may hint at the condition, but by themselves are inconclusive.

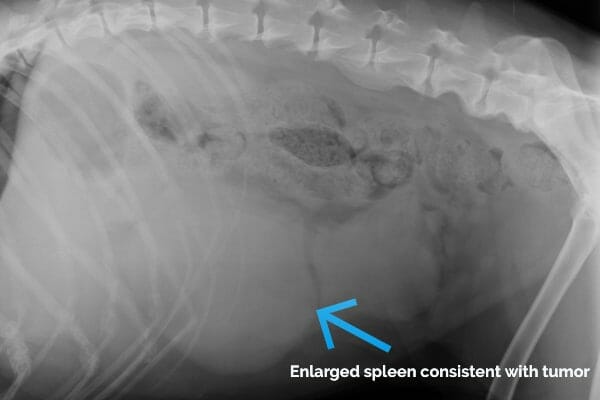

For example, blood work may indicate mild to severe anemia (low red blood cell count), and X-rays might show an abnormal heart, enlarged liver, or enlarged spleen, but that doesn’t automatically equal a cancer diagnosis. Additionally, some tumors are too small to recognize and go undetected until a dog presents with life-threatening symptoms.

Dogs diagnosed with a tumor that is suspected to be a hemangiosarcoma have several treatment options. Your vet will be able to explain each option and provide realistic expectations to help you decide what is best for your dog.

After a tumor is found, your vet may suggest surgery to remove the tumor, preferably before it ruptures. If the tumor is in the spleen, your vet will remove the entire spleen and submit it to a laboratory to reach a final diagnosis.

It is important to send the tumor to the laboratory because not all tumors are cancerous. Hemangiosarcoma in dog is a malignant (cancerous) tumor, but there’s always the chance the splenic enlargement is due to a benign tumor or process—which are “good” diagnoses.

It’s important to note that tumors on the liver and the heart are more difficult to remove surgically, as are hemangiosarcoma tumors that have spread to other body parts like the lungs, kidneys, brain, and spinal cord.

Chemotherapy is recommended in cases where surgery is not an option. Dogs with severe anemia will need blood transfusion(s), and all hemangiosarcoma patients need to avoid blood-thinning medications. Twice daily use of a unique herbal supplement known as Yunnan Baiyao may help prevent further bleeding.

When determining the outcome for cancer in dogs, veterinarians look at the median survival time (MST). According to the National Cancer Institute, MST is the “length of time from either the date of diagnosis or the start of treatment for a disease, such as cancer, that half of the patients in a group of patients diagnosed with the disease are still alive.” In other words, MST represents how long patients (or our beloved dogs) survive with a disease after a certain treatment.

I’m sad to share that dogs with hemangiosarcoma who undergo both surgery and chemotherapy have a MST of six to nine months while those who undergo surgery alone have a MST of two months. Overall, only 29% of dogs diagnosed with hemangiosarcoma survive one year. How long a particular dog survives also depends in part on if their tumor had already metastasized (spread) at the time of diagnosis.

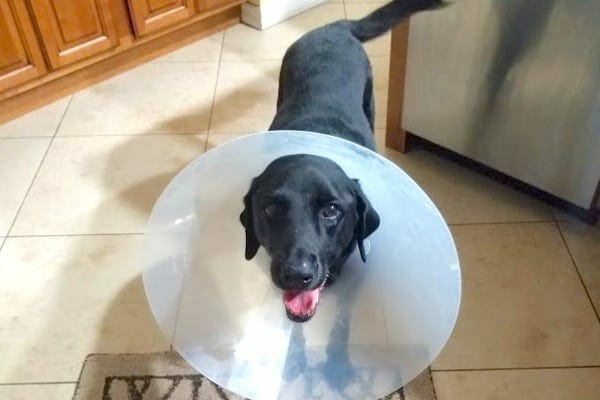

After running a few tests on Lulu that September day, I discovered she was actively bleeding in her abdominal cavity, increasing the odds of a hemangiosarcoma. Because she was severely anemic, surgery was extremely risky. Humane canine euthanasia would have been a loving and logical choice, but I chose surgery to give Lulu one last fighting chance.

A wonderful colleague started a blood transfusion for Lulu and performed her surgery. She found a large tumor on the spleen, the source of Lulu’s bleeding. At the time, we didn’t know if it was a hemangiosarcoma tumor, but because there were abnormal lesions on the liver also, the likelihood was the tumor was malignant — and the cancer had already spread. We submitted her spleen to the pathology lab for testing. A week later, the lab results confirmed her hemangiosarcoma.

Post-surgery, I chose to forego chemotherapy and focus on Lulu’s quality of life. Just like before, I gave her plenty of tasty treats, loads of attention, and gentle games of fetch with her almost every night.

Three weeks after surgery, over the course of several days, Lulu grew increasingly tired, lethargic, and uninterested in her food. My family and I knew it was time. We decided to say goodbye to our beloved dog.

Hemangiosarcoma tumors are among the worst kinds of cancer in dogs. They are difficult to detect on wellness exams and may only become obvious when your dog is in an emergency situation. Hemangiosarcomas usually have a guarded to poor prognosis because they spread quickly or abruptly rupture without any trauma.

By sharing Lulu’s story, I hope you are now better equipped to recognize the signs and seek immediate medical treatment if you find yourself in a similar situation with your beloved canine companion.

While I do miss her dearly, I was happy Lulu could pass peacefully while my family said their goodbyes. She’s left nothing behind but treasured memories and tremendous love for all things Labrador.

If you’re making the difficult decision to say goodbye to your beloved dog, you may find comfort and answers in these resources:

What are the clinical signs?

Clinical signs depend on the location of disease. For internal tumors, signs usually relate to the severity of internal bleeding that occurs secondary to tumor rupture. Signs can be as subtle as intermittent lethargy or weakness with decreased interest in exercise/activities and appetite, or as severe as collapse, with or without a distended abdomen, severe respiratory signs, and/or pale gums.

Superficial skin tumors typically appear as a red to purple colored region of skin or bump that may bruise or bleed spontaneously. When tumors occur under the skin, a soft or firm swelling may be palpable. However, it is impossible to tell from appearance or feel whether a skin mass is benign or malignant.

Treatment options available and prognosis

Complete surgical excision is the ideal treatment for hemangiosarcoma. For certain tumors, this may be the only necessary treatment option. Chemotherapy to delay the progression of metastatic disease is recommended for surgically excised tumors with high rates of spread, seen most frequently in the following sites: spleen, liver, heart, bone, and tumors located beneath the skin/within muscle.

For patients with evidence of metastasis at the time of diagnosis, or for patients where surgical removal of the primary tumor is not possible (e.g. some cardiac tumors) chemotherapy may be an option to slow the progression of metastatic disease and maintain a good quality of life though prognosis is guarded. Additionally, when surgical removal is not an option, palliative radiation therapy may be considered. Incompletely excised skin tumors can be treated with definitive radiation to prevent or delay recurrence.

Splenic Hemangiosarcoma in Dogs

In following article, we describe the current state of knowledge for canine hemangiosarcoma, including what it is, why it may happen, and how it can be managed. In addition, we present recent findings from our programs that promise to help us improve our ability to diagnose, treat, and prevent this disease.