Clubs Offering:

One day in 1938, soon after Nazi Germany annexed Austria, Adolf Hitler sent a car to his hometown of Linz to pick up Rudolphina and Rudolph Menzel.

The Jewish couple – a psychologist and physician, respectively, who were also internationally known dog trainers – knew what their destination would be if they complied.

It would not be a concentration camp, the all-too-final fate of so many of their fellow Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. Instead, it would be a Germany Army camp, where the Menzels would move into a luxury cabin designed for military officers, and join the senior staff to study and train war dogs – the same dogs that would be used to hunt down and help exterminate people like themselves.

With the help of a senior member of the S.S. who was also a family friend, the Menzels escaped to safety across the border with a few dogs in tow. They boarded a ship, and on the eve of Rosh Hashanah reached Palestine.

There, they began the work of rebuilding a homeland for the Jewish people. And in the process, Rudolphina Menzel gave them back something that they did not even know they were missing: a hardy, desert-dwelling canine that she named the Canaan Dog.

Rudolphina Menzel was an unlikely candidate to be a worldwide dog authority. As a four-year-old, she was bitten by a puppy, an incident that only stoked her desire to understand what motivated these furry creatures. Raised in a wealthy family that considered dogs unsanitary and refused to allow one in the house, she gave her allowance to neighbors so they would care for the stray dogs she rescued.

At their luxurious villa in the 1920s, the Menzels founded a dog-training school. There, the two conducted research and wrote books on canine behavior and scenting ability. Rudolphina taught then-popular military breeds like German Shepherds, Doberman Pinschers, and Boxers – the latter of which she also bred – to guard, attack, and track. Though Austrian born, the Menzels were an ardent Zionists, and the dogs they trained for the German and Austrian armies were taught to obey commands only in Hebrew, a bitter irony considering how they were used as the Nazi regime progressed.

For more than a decade before she fled Austria, Rudolphina Menzel had been working with Zionists in Palestine, selling them trained dogs; hosting members of the Haganah, the precursor to the Israel Defense Forces, so they could learn her training methods, and giving courses at kibbutzes on training guard dogs.

In encouraging the use of dogs on new Jewish settlements in Palestine, Rudolphina Menzel’s goal wasn’t just to provide them with effective security. For her, the dogs were also a symbolic bridge between the Jewish ghettos of Europe and their new life in the Levant.

“In our veins flows the blood of many generations who spent their whole lives in the stifling cities, and the blood of many generations before them who never left the alleys of the ghetto,” the Menzel wrote in a 1939 book. “They were far from the soil, far from animals. Every animal was alien to them and the dog was most alien of all.”

That was due in no small part because the dog had been associated with Jewish persecution for centuries. “It was used as an escort and an aide to persecutors and oppressors,” they wrote. “At the order of the squire, the dog attacked and drove off the Jewish peddler. The dog was the companion of the rulers who decided the fate of the Jews, whether they would live or die.”

With their arrival in Palestine on the eve of World War II, the Menzels began training service and guard dogs for the Haganah. As she did in Austria, Rudolphina Menzel established an institute to train and study dogs for military and later agricultural purposes. The dogs she trained searched for wounded soldiers, detected and transported ammunition, picked up on radio communications, and carried messages across kilometers. One of her greatest achievements was training dogs to locate land mines by identifying the scent of the loose, different-smelling soil that covered them.

As her training progressed, Rudolphina Menzel found that traditional guarding breeds struggled in the harsh desert climate. The solution, she decided, were the local, semi-wild pariah dogs that lived on the outskirts of human settlements and with the nomadic Bedouins of the desert.

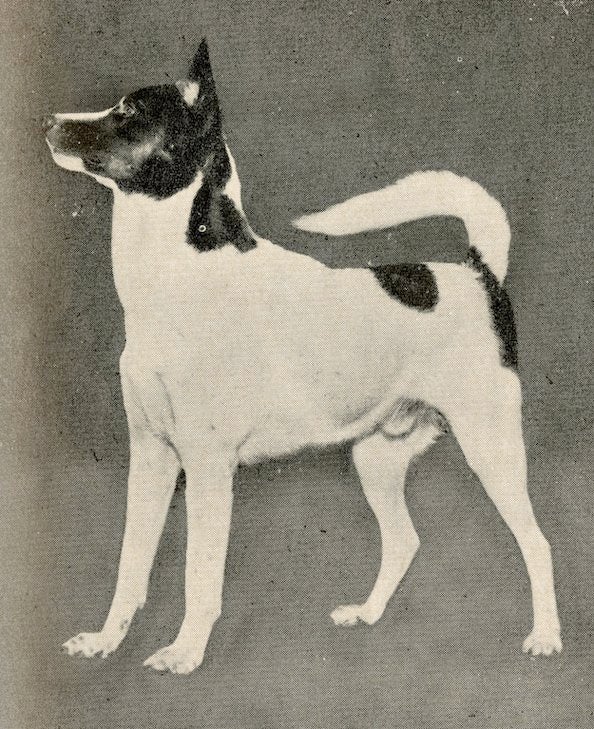

With its light, agile physique and medium size, the Canaan Dog was clearly built for survival in such an arid environment, with the ability to survive high temperatures with little available water. As Rudolphina was to find out, though the dogs were reserved with strangers and quite independent, they nonetheless took to human companionship rather readily, and could be easily trained.

Archeological evidence shows that the prick-eared, curled-tailed dogs that Rudolphina came to call Canaan Dogs had existed in the area for millennia. An ancient dog cemetery in Ashkelon, Israel, dating from the fifth to third centuries BC, contains the remains of more than 1,300 Canaan-like dogs, most of them puppies, positioned their sides, tails deliberately tucked between their legs – evidence, perhaps, that they had been used in religious rituals, with adults dogs theoretically spared so that they could be bred.

Jewish tradition holds that when the Israelites were forced to leave their ancient homeland during the pre-Roman Diaspora, the dogs they left behind melded into the desert and became feral. Rudophina Menzel’s challenge was to find a way to bring them back.

Treking out into the Negev Desert, Rudolphina lured adult dogs with food, and also managed to collect entire litters of puppies. The first adult dog she captured after six months was named Dugma, whose name fittingly translates as “example.” Despite being, in her words, “especially mistrustful,” after a few weeks of training Dugma was tractable enough to accompany her into town on the bus.

Like most things in the Middle East, Israel’s national dog breed—the Canaan dog—has been around for a very, very long time. Adorably occupying an ecological niche based on waste from humans, these dogs are pretty much as canonized as it gets.

Though the nationally-recognized breed numbers between only 2,000 to 3,000 in the world today, we can thank the fact of their continuing survival to Viennese cynologist (“dogologist,” in more fun parlance) Dr. Rudolphina Menzel.

In the 1930s, Dr. Menzel was asked by the Haganah, the paramilitary Jewish forces of pre-State Israel, to build a service dog organization. Finding standard breeds inadequate for complicated tasks, she turned to the pariah doggy for training and breeding, relying on their strong survival instincts. Years later, an American immigrant named Myrna Shibboleth created Jerusalem’s famous, former Shaar Hagai Kennel, which she ran for forty years — and wrote about — until losing her lease earlier this year.

According to archaeologists, pretty much anytime a dog was mentioned in the Torah, the reference was to the Canaan dog. And evidence bears this out: First-century rock carvings in Sinai show the pup in its biblical splendor—and, in 1987, the largest dog cemetery in the ancient world was unearthed in Ashkelon, revealing 700 Canaan dog skeletons dating back 2,500 years.

These days, you can find Canaan dogs at the edges of Bedouin camps in the desert, in the homes of choosy Tel Avivians—or, of course, on the award podium.

The Canaan Dog quickly earned their stay and proved worthwhile as working dogs, and so after World War II, Dr. Menzel began a program to train and breed the dogs as guide dogs for the blind. These days, Canaan dogs make excellent competitors for dog sports and make even better companion pets.

The Canaan Dog may have a symmetrical mask either over the eyes and ears or over the entire head, particularly if the rest of the dog is predominantly white. In general, this breed has a clean outline with a wedge-shaped head, low-set, erect ears, and a high-set brush tail that curls.

Dogs that look similar to Canaans appear on artifacts from 4,000 years ago, although it’s unclear exactly when the breed came into existence. Canaan history changed in the year 70 when Israelites were driven out by the Romans, and their dogs, with nowhere to go and no one to care for them, traveled into the Negev Desert. They survived there, without the help of humans, until the 20th century.

The Canaan Dog—the national dog of Israel—has a fascinating history that has helped it evolve the traits that are characteristic of the dog today. They are sensitive and affectionate with their family, but they can be territorial and wary of strangers or new things because of their background. Proper training and socialization are essential for this breed.

The Canaan Dog is an active breed that requires moderate exercise each day to stay healthy and happy. They are highly trainable, and so they do well with dog sports like tracking and herding. And daily walks will keep them happy, too. Remember to always keep this breed on a leash or in a secure, fenced-in area.

Rabbi Israel Yakobov – DOGS & Pets According to Kabalah

The owner of the kennel specializing in the Canaan dog says it would be difficult to find a replacement site and the court order threatens the breed.

The only kennel in the world specializing in raising Israel’s national dog breed, the Canaan, has been ordered to vacate the premises west of Jerusalem out of which it has operated since 1970. The eviction order was issued by Jerusalem Magistrate’s Court at the request of the Israel Land Authority.

The owner of the kennel, United States-born Myrna Shiboleth, a world expert in the Canaan dog, has been working to promote the survival of the breed, thought to be one of the oldest of dog breeds. The walls of her home are studded with dozens of trophies that she and her kennel have won at dog shows around the world.

Although there are other kennels that breed the dog, hers is the only one to specialize in the breed. Underlining what she deems the special nature of the Canaan, she said it is an original, “natural” breed whose DNA has been maintained as it was before domestication by humans, unlike breeds that have been developed in recent centuries, which she said have produced dogs that suffer from a range of medical and genetic problems.

The Canaan dogs that Shiboleth breeds are among the oldest natural breeds in the world and the only dog whose origins can be traced to the Middle East. It might also be argued that the breed was the first adopted by human beings and that it is referred to in the Bible. The Canaan line has been maintained over the generations because the canines were used as guard dogs at tent encampments of nomadic Bedouin around the Middle East. Some of the breed can still be found living in the wild.

It is considered the ideal guard dog, tough in appearance but not aggressive. But like other rare breeds, it is threatened by the small gene pool of the dogs that remain.

Shiboleth’s kennel at Sha’ar Hagai is on a site off the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway that got its start during the period of the British Mandate. Shiboleth settled there in the 1970s specifically to set up a Canaan dog kennel. For the next 17 years, she lived there with her family without electricity or running water and raised hundreds of Canaan dogs, a population that became a significant portion of all the breed. Over time, some other families joined her at the site in buildings that were already there.

Seven families currently live there, including the family of Shiboleth’s daughter. Initially the families rented their homes from the Mekorot water company, which was the successor to the British Mandatory water company at the site. It turned out, however, that the Israel Land Authority, or as it was previously known, the Israel Land Administration, owned the land.

About four years ago, the ILA sued Shiboleth and the other residents on the site, demanding that they vacate the premises. About a week and a half ago, Jerusalem Magistrate’s Court Judge Dorit Feinstein granted the request and ordered Shiboth and the 13 other occupants, and the kennel, to leave within 90 days.

For her part, however, Shiboleth says the Canaan dog should be seen as an Israeli natural asset and contends that the government should invest in the preservation of the breed for coming generations, just as it invests in protection of other natural assets.

In recent weeks she has appealed to the public for financial assistance through a crowdfunding website. Contributors have so far donated more than $13,000 to fund an appeal of the eviction order.

“I have no pension, and no savings. I just want a place to establish the kennel and it’s very hard to find such a place because no one wants a kennel nearby,” she said. “I don’t want to think about the possibility that I will have to leave.”