Redington wanted to carry it further, to both preserve sled dog culture and maintain the historical Iditarod Trail that stretched between Seward and Nome. After lengthy discussions with fellow mushers, the first Iditarod race was held in 1973. To this day, racers stop at checkpoints located near old gold rush camps during the 1,000-mile-plus race.

The Iditarod is the best-known race of Alaska’s official state sport, but there are dozens of dog races that take place during Alaska winters. Once a basic form of transportation, this popular activity has evolved into a recreational and competitive activity for both residents and tourists. Here’s more about how dog mushing became Alaska’s favorite sport!

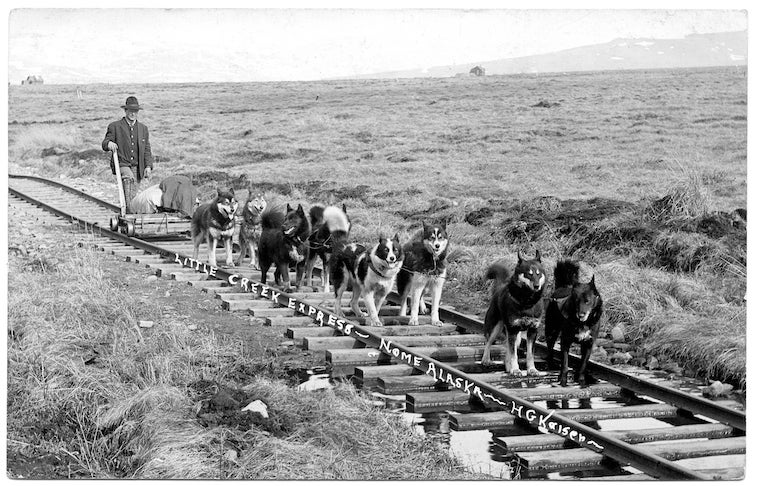

Gold brought settlers to Alaska in droves in the 1890s. In 1908, government employees adopted the use of dog sledding to scope out a route from Seward to Nome. It didn’t get much use at first, but when prospectors learned of a gold discovery in the now-abandoned town of Iditarod in Alaska’s interior, the trail became a key route serving the growing number of mining camps in the region. Teams of dog sleds brought in mail and vital cargo to these otherwise unreachable camps. It remained the main mode of transportation until the 1920s when air travel landed on the scene.

Faster transportation modes once again impacted dog sledding when snowmobiles came into wider use, placing the state’s sled dog culture in danger of dying out. Die-hard dog mushers wouldn’t let that happen. In 1964, Dorothy Page, who led a committee planning the celebration of Alaska’s 100th anniversary of establishment as a U.S. territory, came up with the idea of a sled dog race over the historic gold rush route. She gained support from musher Joe Redington, Sr., who worked with her to develop a 56-mile centennial race between Knik and Big Lake.

Now, Alaskan dog mushers have plenty of races to choose from, including the 1,000-mile Yukon Quest International Sled Dog Race, the Open North American Championship Sled Dog Race, the Limited North American Championships, and the fun Gold Run race, which combines skijoring and mushing and welcome all ages of participants.

Clubs Offering:

What does it take to run hundreds of miles across packed ice and frozen terrain, for days and weeks on end, in arctic temperatures? That’s easy: A lot. A lot of grit, guts, and a laser-like focus on getting where you’re going.

What Breeds Make the Best Sled Dogs?

The Samoyed, Alaskan Malamute, Siberian Husky, Chinook are some of the most well-known of the sled-dog breeds, and with good reason.

Sled dogs probably evolved in Mongolia between 35,000 and 30,000 years ago. Scientists think that humans migrated north of the Arctic Circle with their dogs about 25,000 years ago, and began using them to pull sleds roughly 3,000 years ago.

There are historical references to dogs used by Native American cultures dating back to before the first Europeans made land. There were two main types of sled dogs: one kept by coastal cultures and the other by people living in the interior. In the mid-1800s Russian traders following the Yukon River inland and acquired sled dogs from the villages along its shores.

The first formal sled-dog race wasn’t held until 1850, from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to St. Paul, Minnesota. But sled dogs’ place in human history goes back thousands of years and served a much greater purpose than simple entertainment. Sled dogs served as a primary means of communication and transportation in harsh arctic weather conditions. Some scholars, in fact, believe that human survival in the arctic would’ve been impossible without the assistance of sled dogs. There are many significant moments in history in which sled dogs played an important role. A few notable ones over the last two centuries include:

The late 1800s and early 1900s was nicknamed the “Era of the Sled Dog.” After that, the hearty breeds worked at a variety of jobs, until airplanes, highways, trucks, and snowmobiles effectively put them out of work. (Sled dogs today are still used by some rural communities, especially in areas of Alaska and Canada, and throughout Greenland).

But they didn’t stop mushing once their jobs dried up. Sled-dog breeds and their outdoorsy owners mush for recreational purposes, and the fanatically devoted teams participate in events like the Iditarod and the Yukon Quest. Billed as the “World Series of mushing events” the Iditarod is 1,100 miles of sheer endurance, spanning about 10 or 11 days, depending on the weather.

It begins with a ceremonial launch in Anchorage, Alaska, the morning of the first Saturday in March, with mushers running 20 miles to Eagle River along the Alaskan Highway, giving spectators a chance to see the dogs and their mushers. The teams are then loaded onto trucks and driven 30 miles to Wasilla for the official start of the race. The winning team takes home a $50,000 prize. That’s a lot of premium kibble.

Perhaps the most famous sled dog of all was Balto, a jet black Siberian Husky, who was the lead dog of the sled dog team that carried diphtheria serum on the last leg of the relay to Nome during the 1925 diphtheria epidemic. There was serum in Nenana, but the town was 700 miles away, and inaccessible except by dog sled. A relay was set up, and 20 teams pulled together. Six days later the lifesaving serum reached Nome.

In 1995, Universal Pictures released the movie “Balto,” based on his life. It earned three out of four stars from the most famous film critic of the day, Roger Ebert. Today a bronze statue in Balto’s honor stands in Central Park.

While the lead dog of the 53-mile final leg, Balto, would become famous for his role in the run, many argue that it was Siberian Husky lead dog Togo, who was the true savior of the day. All told, the 12-year-old Togo traversed an astounding 264 miles, compared to an average of 31 miles each for the other teams.

Over time, with the help of historians, Togo began to garner the recognition he deserved. In 2001, Togo received his own statue in NYC’s Seward Park. In 2019, his story was retold in the riveting Disney+ movie Togo, starring Togo’s own descendant Diesel as the namesake Siberian.

Sled Dogs: More Than Meets the Eye | National Geographic

The Iditarod is the best-known race of Alaska’s official state sport, but there are dozens of dog races that take place during Alaska winters. Once a basic form of transportation, this popular activity has evolved into a recreational and competitive activity for both residents and tourists. Here’s more about how dog mushing became Alaska’s favorite sport!

For hundreds of years, nomadic Alaskan natives used dogs to help move supplies in both the summer and winter. Dogs were also vital in hunting and in helping keep watch for bears and other dangers. As sleds came into use in Alaska’s interior, Alaskan natives began to breed dogs that had the agility necessary for pulling the sleds as well as the strength for pulling heavy loads.

Favorite dog sledding breeds have included malamutes – native to Alaska – and Siberian Huskies. Each breed has the strength and furry coat needed to endure Alaska’s winters. But today, the modern Alaskan husky – which is bred from malamutes, huskies and other dog species – is the sled dog favorite of mushers who race. The genetic lineage of these dogs gives them the strength and agility of traditional breeds as well as the endurance needed to stay healthy over long distances.

Gold brought settlers to Alaska in droves in the 1890s. In 1908, government employees adopted the use of dog sledding to scope out a route from Seward to Nome. It didn’t get much use at first, but when prospectors learned of a gold discovery in the now-abandoned town of Iditarod in Alaska’s interior, the trail became a key route serving the growing number of mining camps in the region. Teams of dog sleds brought in mail and vital cargo to these otherwise unreachable camps. It remained the main mode of transportation until the 1920s when air travel landed on the scene.

But the Iditarod Trail had a revival in 1925: When a diphtheria outbreak ravaged the city of Nome, flying life-saving serums into the town was impossible because of the dangerous winter weather. A series of dog sled teams instead carried the serum from the rail station in Nenana to Nome – a distance of nearly 700 miles – making history and helping to inspire the Iditarod Race we know today.

Faster transportation modes once again impacted dog sledding when snowmobiles came into wider use, placing the state’s sled dog culture in danger of dying out. Die-hard dog mushers wouldn’t let that happen. In 1964, Dorothy Page, who led a committee planning the celebration of Alaska’s 100th anniversary of establishment as a U.S. territory, came up with the idea of a sled dog race over the historic gold rush route. She gained support from musher Joe Redington, Sr., who worked with her to develop a 56-mile centennial race between Knik and Big Lake.

Redington wanted to carry it further, to both preserve sled dog culture and maintain the historical Iditarod Trail that stretched between Seward and Nome. After lengthy discussions with fellow mushers, the first Iditarod race was held in 1973. To this day, racers stop at checkpoints located near old gold rush camps during the 1,000-mile-plus race.

Now, Alaskan dog mushers have plenty of races to choose from, including the 1,000-mile Yukon Quest International Sled Dog Race, the Open North American Championship Sled Dog Race, the Limited North American Championships, and the fun Gold Run race, which combines skijoring and mushing and welcome all ages of participants.

Some modern-day mushers have mixed tourism with racing, welcoming curious visitors to their kennels to see the dogs and learn more about this special Alaska sport. When you’re staying at a Westmark Hotel, be sure to ask our friendly staff about day excursions to meet some of these agile canine athletes where they live and train.